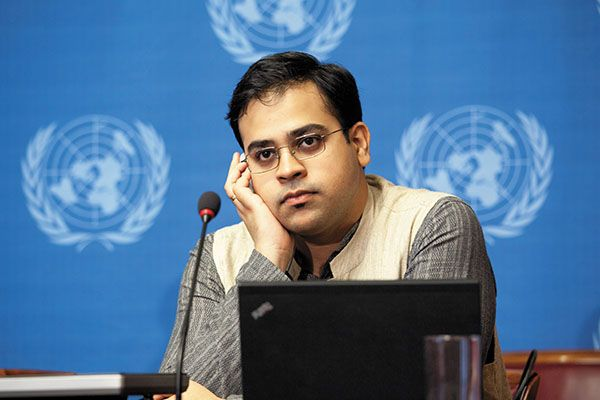

Pranesh Prakash: Influencing India’s IP Laws

-

Access to Knowledge

9 April 2024

Samar Srivastava’s article was published in Forbes India Magazine on February 15, 2014.

At an age where his contemporaries are still junior litigators and aspiring lawyers, Pranesh Prakash, 28, is already a recognisable name in the filed of legal activism.

In 2013 he worked with the World Intellectual Property Organization to draft a treaty for the blind. It provides for an exception to copyright laws so that books can be converted into accessible formats for the blind and visually impaired, and exchanged across borders.

For Prakash the treaty capped a signal achievement in intellectual property and copyright—an area he has been working in since graduating from the National Law School, Bangalore. In his closing speech at the diplomatic conference at Marrakesh, Morocco, Prakash said: “When copyright doesn’t serve public welfare, states must intervene… Importantly, markets alone cannot be relied upon to achieve a just allocation of informational resources, as we have seen clearly from the book famine that the blind are experiencing.”

Prakash’s work on intellectual property has brought him recognition through affiliations: He is an Access to Knowledge Fellow at the Information Society Project at Yale Law School. In 2012, he was selected as an Internet Freedom Fellow by the US State Department.

“I was always interested in doing public interest work,” says Prakash. An internship with activist lawyer Rajeev Dhawan cemented his desire. Prakash is now prominent in a line of thinkers working in the area of freedom of expression, internet governance and intellectual property.

It is clear that existing laws in these areas are inadequate and a new jurisprudential setup needs to evolve. For example, the same standards often apply to print and internet media; they fail to recognise that, say, tweets have a different impact than newspapers headlines.

Prakash’s criticism of governments blocking websites stood out, but his recommendations were not accepted. He proposed that all intermediaries, like the ISP and the domain host, not be bunched, and separate standards be imposed on them, based on their editorial role in content creation.

“What distinguishes his work is the impact it has on the public at large,” says Gautam John, head, Karnataka Learning Partnership at the Akshara Foundation. “His work in the area is cutting edge. There is no one doing that work.”

Then there is his work with Section 66A of the IT Act. Under the section, anyone who sends false, offensive or inappropriate content by a computer or communication device can be punished with three years of imprisonment. This section has been misused by the police. Prakash has long argued that the law must be more specific in what it defines as offensive, and that the government needs to engage more with civil society and industry to end the antagonistic and selective manner in which the law is imposed.

Efforts of the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS), Bangalore, where Prakash is policy director, have resulted in rules being amended. Now, only officers of the rank of DCP and above can make an arrest. CIS, set up in 2008, has also made representations on the copyright law to Parliamentary Standing Committees.

Prakash’s activism has had another significant effect on intellectual property in India. By a 2008 Bill, the government had tried to privatise publicly-funded intellectual property. Prakash was part of a sustained campaign against the Bill, and in 2011 it was shelved.