The National Health Stack: An Expensive, Temporary Placebo

-

Internet Governance

Torsha Sarkar,Swaraj Barooah,Murali Neelakantan,Swagam Dasgupta

13 August 2018

The article was published by Bloomberg Quint on August 6, 2018.

However, the next ten years would see the scheme meet with constant criticism about its poor management and immense expenditure; and after a gruelling battle for survival, including spending £20 billion and having top experts on board, the NPfIT finally met its end in 2011.

Fast forward eight years — the Indian government’s public policy think tank, NITI Aayog, is proposing an eerily similar idea for the much less developed, and much more populated Indian healthcare sector. On July 6, the NITI Aayog released a consultation paper to discuss “a digital infrastructure built with a deep understanding of the incentive structures prevalent in the Indian healthcare ecosystem”, called the National Health Stack. The paper identifies four challenges that previous government-run healthcare programs ran into and that the current system hopes to solve. These include:

- low enrollment of entitled beneficiaries of health insurance,

- low participation by service providers of health insurance,

- poor fraud detection,

- lack of reliable and timely data and analytics.

The current article takes a preliminary look at the goals of the NHS and where it falls behind. Subsequent articles will break down the proposed scheme with regard to safety, privacy and data security concerns, the feasibility of data analytics and fraud detection, and finally, the role of private players within the entire structure.

The primary aim of any digital health infrastructure should be to compliment an existing, efficient healthcare delivery system.

As seen in the U.K., even a very well-functioning healthcare system doesn’t necessarily mean the digitisation efforts will bear fruit.

The NHS is meant to be designed for and beyond the Ayushman Bharat Yojana — the government’s two-pronged healthcare regime that was introduced on Feb. 1. Unfortunately, though, India’s healthcare regime has long been in the need of severe repair, and even if the Ayushman Bharat Yojana works optimally, there are no indications to show that this will miraculously change by their stated target of 2022. Indeed, experts predict it would take at least a ten-year period to successfully implement universal health coverage. A 2013 report by EY-FICCI stated that we must consider a ten-year time frame as well as allocating 3.5-4.7 percent of the GDP to health expenditure to achieve universal health coverage.

However, as per the current statistics, the centre’s allocation for health in the 2017-18 budget is Rs 47,353 crore, which is 1.15 percent of India’s GDP.

Patients wait for treatment in the corridor of the Acharya Tulsi Regional Cancer Treatment & Research Institute in Bikaner, Rajasthan, India. (Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg)

Along with the state costs, India’s current expenditure in the health sector comes to a meagre 1.4 percent of the total GDP, far short of what the target should be. Yet, the government aims to attain universal health coverage by 2022.

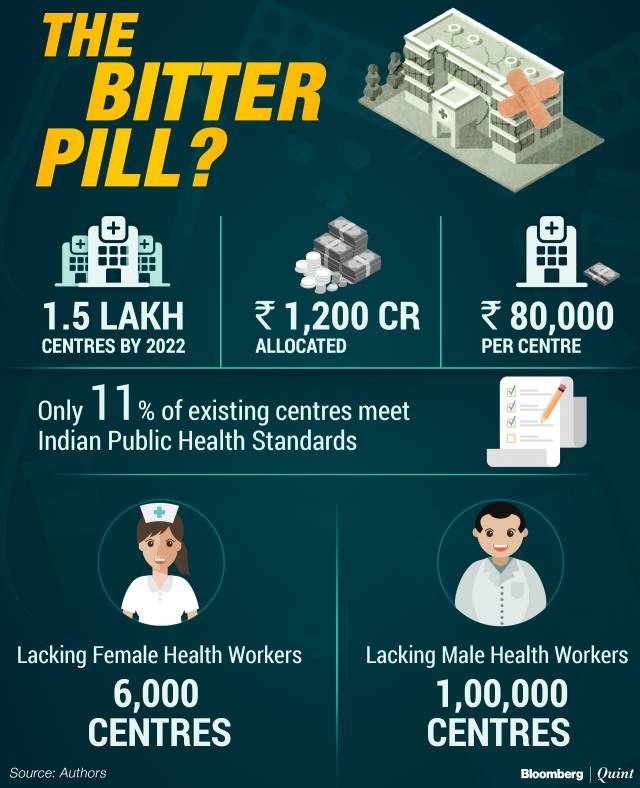

In the first of its two-pronged strategy, the Ayushman Bharat Yojana aims to establish 1.5 lakh ‘Health and Wellness Centres’ across the country by 2022, which would provide primary healthcare services free of cost.

However, the total fund allocated for ’setting up’ these centres is only Rs 1,200 crore, which comes down to a meagre Rs 80,000 per centre.

It is unclear whether the government plans to establish new sub-centres, or improve the existing ones. Either way, a pittance of Rs 80,000 is grossly insufficient. As per reports, among the 1,56,231 current health centres, only 17,204 (11 percent) have met Indian Public Health Standards as of March 31, 2017. Shockingly, basic amenities like water and electricity are scarce, if not, absent in a substantial number of these centres.

At least 6,000 centres do not have a female health worker, and at least 1,00,000 centres do not have a male health worker.

A woman holds a child in the post-delivery ward of the district hospital in Jind, Haryana, India. (Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg)

Even taking the generous assumption that the existing 17,204 centres are in top condition, the future of the rest of these health and wellness centres continues to be bleak.

In truth, both limbs of the Ayushman Bharat strategy remain oblivious to the reality of the situation. The goals do not take into account the existing problems within access to healthcare, nor the relevant economic and social indicators that depict a contrasting reality.

Therefore, the fundamental question remains: if there is no established, well-functioning healthcare delivery system to support, what will the NHS help?

NHS: What Purpose Does It Serve?

The ambitious scope of the National Health Stack consultation paper aside, the central problem plaguing the Indian healthcare system, i.e, delivery, and access to healthcare, remains unaddressed. The first two problems that the NHS aims to solve focus solely on increasing health insurance coverage. However, very problematically, the document does not explicitly mention how a digital infrastructure would lead to rising enrollment of both beneficiaries and service providers of insurance.

This goal of increasing enrollment without a functioning healthcare system could result in two highly problematic scenarios.

Either health and wellness centres will effectively act as enrollment agencies rather than providers of healthcare, or the government would fall back on its ‘Aadhar approach’ and employ external enrollment agents.

The former approach runs a very real risk of the health and wellness centres losing focus on their primary purpose even while statistics show them as functioning centres – thus negatively impacting even the working centres. The latter approach is at a higher risk of running into problems akin to the case of Aadhaar enrollment, such as potential data leakages, identity thefts and a market for fake IDs. Even if we somehow overlook this and assume that the NHS would help increase insurance coverage without additional problems, the larger question still stands: should health insurance even be the primary goal of the government, over and above providing access to healthcare? And what effect will this have on the actual delivery of healthcare services to the common citizen?

A lone patient sleeps in the post operation recovery ward of the district hospital in Jind, Haryana, India. (Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg)

Should Insurance Be A Primary Objective Of The Indian Government?

Simply put, the answer is no, because greater insurance coverage need not necessitate better access to healthcare. In recent years, health insurance in India has been rising rapidly due to government-sponsored schemes. In the fiscal year 2016-17, the health insurance market was prized to be worth Rs 30,392 crore. Even with such large investments in insurance premiums, the insurance market accounts for lesser than 5 percent of the total health expenditure.

Furthermore, previous experiences with government-sponsored health insurance schemes have proven that there is little merit to such an expensive task.

For instance, the government’s earlier health insurance scheme, Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana, was predicted to be unable to completely provide ‘accessible, affordable, accountable and good quality health care’ if it focussed only on “increasing financial means and freedom of choice in a top-down manner”.

These traditional insurance-based models are characterised by problems of information asymmetry such as ‘moral hazard’ — patients and healthcare providers have no incentive to control their costs and tend to overuse, resulting in an unsustainable insurance system and cost inflation. Any attempt to regulate providers is met with harsh, cost-cutting steps which end up harming patients.

On another note, some diseases which are responsible for the most number of deaths in the country — including ischaemic heart diseases, lower respiratory tract infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, tuberculosis and diarrhoeal diseases — are usually chronic conditions that need outpatient consultation, resulting in out-of-pocket expenses.

Patients wait at the Head and Neck Cancer Out Patient department of Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai, India. (Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg News)

Even though the government has added non-communicable diseases under the ambit of the health and wellness centres, there are still reports stating that for some of the most impoverished, their reality is that 80 percent of the time, they have to cover their expenses from their pocket. This issue in all probability will continue to exist since the status and likelihood for these centres to be successful itself is questionable.

It is clear, that in the current scheme of things, this traditional insurance model of healthcare cannot benefit those it is meant for.

If this is the case, why has the NHS built its main objectives around insurance coverage rather than access to healthcare? It is imperative that we question the legitimacy of these goals, especially if they indicate the government’s intentions to push health insurance via the NHS above its responsibility of delivering healthcare. The government’s thrust for a digital infrastructure shows tremendous foresight, but at what cost? Even the clear goal of healthcare data portability has very little benefit when one understands that this becomes an important goal only when one has given up on ensuring widespread accessible healthcare. Once the focus shifts from using technology needlessly to developing an efficient and universally accessible healthcare delivery system, the need for data portability dramatically reduces. The temptation of digitisation and insurance coverage cannot and should not blind us from the main goal — access to healthcare. The one lesson that we must learn from the case of the U.K. is that even with a well-functioning healthcare delivery system, a digital infrastructure must be introduced very thoughtfully and carefully. In our eagerness to leapfrog with technology, we must not mistake a placebo for a panacea.

Murali Neelakantan is an expert in healthcare laws. Swaraj Barooah is Policy Director at The Centre for Internet and Society. Swagam Dasgupta and Torsha Sarkar are interns at The Centre for Internet and Society.