From Taboo to Beautiful – Menstrupedia

-

RAW

Denisse Albornoz

30 April 2014

CHANGE-MAKER: Tuhin Paul, Aditi Gupta and Rajat MittalORGANIZATION: MenstrupediaMETHOD OF CHANGE: Storytelling and comicsSTRATEGY OF CHANGE: To shatter the myths and misunderstandings surrounding menstruation, by delivering accessible, informative and entertaining content about menstruation through different media.

Most of us think we know what menstruation is; except…we don’t. Many of my male friends still cringe at the mention of the phrase “I’m on my period”, or use it as a derogatory justification for my occasional cranky mood at the office: “It’s that time of the month, isn’t it?” Poor menstruation has been the culprit of femininity; always bashful, tiptoeing for five days straight, trying its best to remain incognito. The social venture Menstrupedia is committed to change this. Aditi, Tuhin and Rajat want to shift how we look at menstruation and remove the stigma that haunts the natural, self-regulation process women undergo to keep their bodies healthy and strong to sustain life in the future.

Now, if you are already wondering what menstruation has to do with internet and society, just wait for it. This post manages to bring art, punk, menstruation and technology together, all within the scope of the Making Change project! Before though, we shall start with some definitions. Let us first lay conceptual grounds about menstruation and Menstrupedia, to then locate and unpack their theory of change.

What is menstruation?

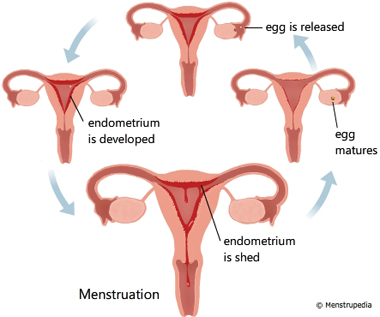

It can be defined as:

Menstruation is the periodic discharge of blood and mucosal tissue (the endometrium) from the uterus and vagina. It starts at menarche at or before sexual maturity (maturation), in females of certain mammalian species, and ceases at or near menopause (commonly considered the end of a female’s reproductive life).

And it looks something like this:

But, I believe, most women will agree the following are much more accurate depictions of the spectrum of thoughts, emotions and sensations that menstruation spurs:

The Beauty of RED

My Periods: A Blessing or a Curse

By Naina Jha

| My periods Are a dreadful experience Because of all the pain. Myths and secrets make it a mystery What worsens it most though, are members of my family Especially my mother, who always make it a big deal They never try to understand what I truly feel I face all those cramps and cry the whole night long None of which is seen or heard or felt by anyone. |

Instead of telling me, what it is, They ask me to behave maturely instead. Can somebody tell me how I am supposed to Naturally accept it? My mother asks me to stay away from men And a few days later, she asks me to marry one! When I ask her to furnish the reason behind her haste She told me that now that I was menstruating, I was grown up and ready to give birth to another. |

I don’t know whether to feel blessed about it Or consider it to be my curse. For these periods are the only reason for me to be disposed. Since my childhood, I felt rather blessed to be born as a girl But after getting my periods now, I’m convinced that it’s a curse… |

Find it in Menstrupedia’s blog.

Despite all this, it is still perceived as a social stigma in society. There is clearly a dissonance between the definition, experience and perceptions around menstruation, that calls for a reconfiguration of the information we are using to define it.

Stigma as a Crisis

However, re-defining ‘menstruation’ is no popular or easy task. The word belongs to a group of contested terminology around womanhood and is the protagonist of its own breed of feminist activism: menstrual activism. 1] Although I would consider many of the stigmas surrounding menstruation to be quite self-explanatory (we’ve all experienced and perpetuated them in one way or another -and if they are not, then you are the product of an obscenely progressive upbringing for which I congratulate your parents, teachers and all parties involved), I will still outline the main reasons why menstruation is a source of social stigma for women, and refer to scholarly authority on the subject to legitimize my rant.

Ingrid Johnston-Robledo and Joan Chrisler use Goffman’s definition of stigma 2] on their paper: The Menstrual Mark: Menstruation as a Social Stigma to explain the misadventures of menstruation:

Stigma: stain or mark setting people apart from others. it conveys the information that those people have a defect of body or of character that spoils their appearance or identity

Among the various negative social constructs deeming menstruation a dirty and repulsive state, this one made a particular echo: “menstruation is] a tribal identity of femaleness”. Menstruation is the equivalent of a rite of passage marking the lives of girls with a ‘before’ and an ‘after’ on how the world sees them and how they see themselves. From the dreaded stain on the skirt and the 5-day mission to keep its poignant color and smell on the down low, to having to justify mood and body swings to the overly inquisitive; menstruation is imagined as inconvenient, unpleasant and unwelcome. As Johnston-Robledo and Chrisler point out: the menstrual cycle, coupled with stigmas, pushes women to adopt the role of the “physically or mentally disordered” and reinforce it through their communication, secrecy, embarrassment and silence (Kissling, 1996).

Why does it matter?

Besides from strengthening attitudes that underpin gender discrimination and attempting against girls’ self-identity and sense of worth, there are other tangible consequences for their development and education. I’m going to throw some facts and figures at you, to back this up with the case of India.

An article published by the WSSCC, the Geneva based Water supply and Sanitation Council, shows the Menstruation taboo, consequence of a “patriarchal, hierarchical society”, puts 300 million women at risk in India. They do not have access to menstrual hygiene products, which has an effect on their health, education (23% of girls in India leave school when they start menstruating and the remaining 77% miss 5 days of school a month) and their livelihoods.

In terms of awareness and information about the issue, WSSCC found that 90% didn’t know what a menstrual period was until they got it. Aru Bhartiya’s research on Menstruation, Religion and Society, shows the main sources of information about menstruation come from beliefs and norms grounded on culture and religion. Some of the related restrictions (that stem from Hinduism, among others) include isolation, exclusion from religious activities, and restraint from intercourse. She coupled this with a survey where she found: 63% of her sample turned to online sites over their mothers for information, 62% did not feel comfortable talking about the subject with males and 70% giggled upon reading the topic of the survey. All in all, a pretty gruesome scenario

Here’s where Menstrupedia comes in

The research ground work attempted above was done in depth by Menstrupedia back in 2009 when the project started taking shape. They conducted research for one year while in NID and did not only find that awareness about menstruation was very low, but that parents and teachers did not know how to talk about the subject.

| Facts about menstruation awareness in India. Video courtesy of Menstru pedia Youtube channel. |

Their proposed intervention: distribute an education visual guide and a comic to explain the topic. They tested out the prototype among 500 girls in 5 different states in Northern India and the results were astonishing.

|

|

A workshop conducted by MJB smriti sansthan to spread awareness about mensuration. Find full album of Menstrupedia Comic being used around India on Menstrupedia’s Facebook page.

“To my surprise, they the nuns] all agreed that until they read the information given in the Menstrupedia comic, even they were of the opinion that Menstruation was a ‘dirty’ and ‘abominable’ thing and they wondered ‘why women suffered from it in the first place’? But after reading the comic book, their view had changed…now they felt that this was a ‘vital’ part of womanhood and there’s nothing to feel ashamed about it! The best part was while this exercise clarified their ideas, beliefs, concepts about menstruation, it also helped me to get over my innate hesitancy to approach such a sensitive issue in ‘public’ and boosted my confidence for taking this up as a ‘mission’ to reach out to the maximum possible girls across the country.”

Ina Mondkar, on her experience of educating young nuns about menstruation.

Testimonial after a workshop held in two Buddhist monasteries in Ladakh.

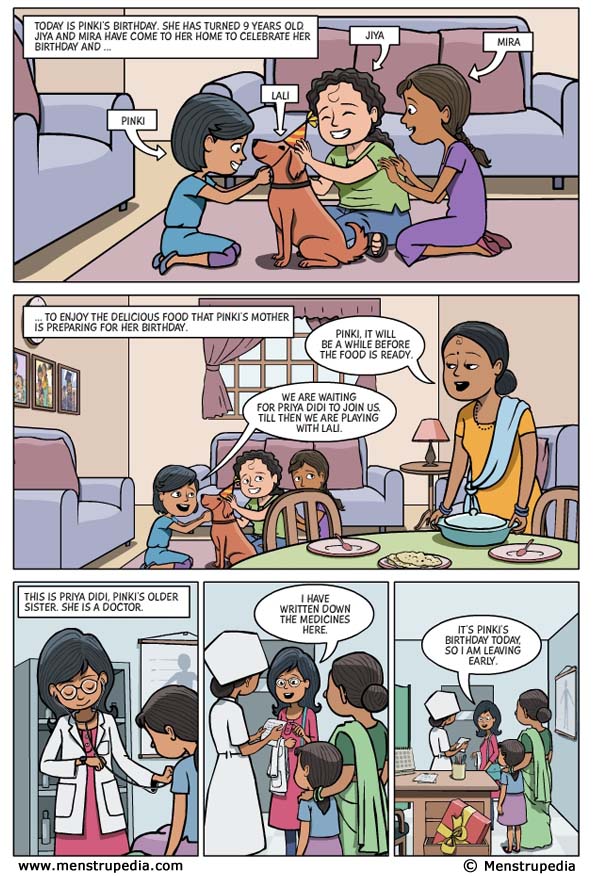

Their mandate today reads: ‘Menstrupedia is a guide to explain menstruation and all issues surrounding it in the most friendly manner.’ They currently host a website with information about puberty, menstruation, hygiene and myths, along with illustrations that turn explaining the process of growing up into a much friendlier endeavour than its stigma-ladden alternatives.

Snipbit of the first chapter. Read it for free here.

Through the comic and the interactions around it, Menstrupedia strives to create a) content that frame menstruation as a natural process that is inconvenient, yes; but that should have no negative effects on their self-esteem and development; and b) an environment where girls can talk about it openly and clarify their doubts.

Technology’s role in the mix

The role of digital technologies basically comes down to scalability. Opposite to The Kahani Project’s views on scaling up, Menstrupedia makes emphasis on using technology to reach a larger audience. Currently they have a series of communication channels enabled by technology that include: a visual quick guide, a Q&A forum (for both men and women), a blog (a platform of self-expression on menstruation), a you tube channel (where they provide updates on their progress) and the upcoming comic.

Upon the question of the digital divide and whether this expands the divide between have and have nots, Tuhin was very set on the idea of producing the same content in both its digital and print form. “parents or schools should be able to buy the comic and give it to their daughters, so whenever they feel like it, they can refer to it”. The focus is on making this material as readily available as possible, in order to overcome the tension between new and old information: “workshops are conducted but the moment they go back home, their mothers impose certain restrictions. It becomes a dilemma. But if you provide The girl] with a comic book, she has something she can take home and educate her mother with”

And here’s why it works

More than the comic book itself, what is truly remarkable about Menstrupedia is Tuhin, Rajat and Aditi’s guts to pick up such a problematic theme in the Indian social imaginary and challenge the entrenched, stubborn beliefs surrounding the issue. The comic book, asides from being appealing to the eye and an accessible format of storytelling (a method we have unpacked in previous posts), fits right into the movement of menstrual activism and what it stands for.

First, it is a self-reliant resource. Once the comic book leaves Menstrupedia’s hands and lands on those of kids and adults, it takes its own journey. The format of the comic is accessible enough for someone to pick it up and learn about menstruation without the intervention or the support of a third party. This makes Menstrupedia’s comic highly flexible and mobile. It can be shared from teacher to child, from mom to daughter, from peer to peer: “it should teach] how to help your friends when they get their period” (Tuhin) However, it has the autonomy to also take roads less travelled: from mom to dad, from child to teacher, from boy to girl. The goal at the end of the day: a self-reliant, solidarity-based community where information circulating about menstruation highlights its capacity to give life and overshadows its traditional stigmatized identity.

This self-reliance is characteristic of previous manifestations of menstrual activism. Back in the 80s, the feminist movement, tightly linked to punk culture, embraced the do it yourself movement,3] that enabled women to materialize personalized forms of resistance. They published zines promoting “dirty self-awareness, body and menstrual consciousness and unlearning shame” through “raw stories and personal narratives” (Bobel, 2006). According to Bobel using the self as an example is a core element in the “history of self-help” within the DIY movement. The role of the Menstrupedia blog is then crucial to sustain the exposure and production of “raw narratives”. Tuhin adds: “We don’t write articles on the blog. It is a platform where people from different backgrounds write about their experiences with menstruation and bring in a different perspective”: For example,

Red is my colour by Umang Saigal

|

Red is my colour, To make you understand, I endeavour, Try to analyse and try to favour. It is not just a thought, but an attempt, To treat ill minds that are curable. When I was born, I was put in a red cradle, I grew up watching the red faces for a girl-children in anger, Red became my favourite, But I never knew, That someday I would be cadged in my own red world. |

Red lover I was, All Love I lost, When I got my first red spots, What pain it caused only I know, When I realized, Red determined my ‘class’

I grew up then, ignoring red, At night when I found my bedsheet wet, All day it ached, All day it stained, And in agony I would, turn insane. |

At times I would think, Does red symbolize beauty or pain? But when I got tied, in the sacred knot, I found transposition of my whole process of thought, When from dirty to gold, Red crowned my bridal course. As I grew old, All my desires vanished and got cold, My mind still in a dilemma, What more than colour in itself could it unfold? What was the secret behind its truth untold? |

Is Red for beauty, or is it for beast? It interests me now to know the least, All I know is that Red is a Transition, From anguish to pride Red is a sensation. Red is my colour, as it is meant to be, No matter what the world thinks it to be, No love lost, one Love found, Red symbolizes life and also our wounds, I speak it aloud with life profound, That red is my colour, and this is what I’ve found. |

Submission to the Menstrupedia blog

‘Self-expression’ is not a concept we usually find side by side with ‘menstruation’; however, if we look at what has been done in the past, we find that Menstrupedia is actually contributing to a much larger tradition of resistance. For instance, Menstrala, by the American artist Vanessa Tiegs. Menstrala is the name of a collection of 88 paintings “affirming the hidden forbidden bright red cycle of renewal”.

Another interesting example is American feminist Gloria Steinem’s4] text If Men Could Menstruate.

“What would happen, for instance, if suddenly, magically, men could menstruate and women could not? The answer is clear: Menstruation would become an enviable, boast worthy, masculine event: Men would brag about how long and how much. Boys would mark the onset of menses, that longed- for proof of manhood,with religious and stag parties.”

Gloria Steinemexcerpt]

Opportunities like these, enable Menstrupedia’s community to actively participate in the reconfiguration of ‘menstruation’ as a concept and as an experience. By exposing new narratives and perspectives on the issue and by disseminating menstrual health information, the community is able to crowd source resistance and dismantle the stigma together.

Making Change through Menstrupedia

The case of Menstrupedia reminds us of Blank Noise because of its approach to change. Both locate their crises at the discursive level and seek to resolve them by creating new forms of meaning-making. They advocate for a reconsideration of ‘givens’, for a self-reflection on our role perpetuating these notions and for resistance against conceptual status quos: be it socially accepted culprits like ‘eve-teasing’, or more discrete rejects like ‘menstruation’. Both seek to dismantle power structures that give one discourse preference over others, and both count with a strong gender dynamic dominating the context where these narratives unfold. They are producing a revolution in our system of meaning making, yet only producing resistance in the larger societal context they inhabit.

On the question of where is Menstrupedia’s action located, Tuhin replied by pinning it at the individual level: “if a person is aware of menstruation and they know the facts, they are more likely to resist restrictions and spread awareness”. However, they still acknowledge the historicity behind menstrual awareness (as knowledge passed down from generation to generation) that precedes the project. While the introduction of Menstrupedia, to an extent, does shake up household dynamics in terms of content, it also provides tools and resources to sustain the traditional model of oral tradition and knowledge sharing within the community.

In terms of their role as change-makers ,Tuhin stated that the possibility to intervene was a result of their socio-economic status and the resources they had at hand as “educated members of the middle class with access to information and communication technologies”. Is this the role the middle class should play? I asked. To which he gave a two fold answer: First, in terms of responsibility of action: “it is a role that anyone can play depending on what kind of expertise they have. It comes to a point where intents of change] cannot be sustained by activism if you want to achieve long term impact” And second, in terms of setting up a resilient infrastructure: “I believe we can create an infrastructure people can use and create models that can help low income groups overcome their challenges and become self-sustainable.” Both answers highlight the need for sustainability in social impact projects, hinting a retreat from wishful thinking upon the presence of technology and a more strategic allocation of skills and resources by middle class and for-profit interventions.

As far the relationship between art, punk, menstruation and technology goes; that was just a hook to get you through the unreasonable length of my blog post, but if anything, it represents an effort to portray the importance of contextuality and interdisciplinary we have been exploring throughout the series. Identifying the use of various mediums and language systems, such as different art forms and modes of self-expression, as well the acknowledgement of the theoretical and social contexts preceding and framing the project, as is feminist activism and the cultural and religious backdrop in India, contribute immensely to fill gaps in the stories of how we imagine change making today; especially at the nascence of new narratives, as we hope is the case for menstruation in a post-Menstrupedia era.

Sources:

Bhartiya, Aru: “Menstruation, Religion and Society” IJSSH: International Journal of Social Science and Humanity. Volume: Vol.3, No.6.

Footnotes

1] Refer to Chris Bobel’s work including New Blood: Third-Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation. Access it here

2] Johnston Robledo and Chrisler made reference to Erving Goffman‘s 1963 work: Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. “According to Goffman (1963), the word stigma refers to any stain or mark that sets some people apart from others; it conveys the information that those people have a defect of body or of character that spoils their appearance or identity Goffman (1963, p. 4) categorized stigmas into three types: “abominations of the body” (e.g., burns, scars, deformities), “ blemishes of individual character” (e.g., criminality, addictions), and “tribal” identities or social markers associated with marginalized groups (e.g., gender,race, sexual orientation, nationality)”.

3] For a short run through on DIY as part of the Punk Subculture, refer to Ian P. Moran’s paper: Punk – The Do-it-Yourself culture.”Punk as a subculture goes much further than rebellion and fashion as punks generally seek an alternative lifestyle divergent from the norms of society. The do-it-yourself, or D.I.Y. aspect of punk is one of the most important factors fueling the subculture.” Access it here.

4] Gloria Steimen is a journalist, and social and political activist who became nationally recognized as a leader of, and media spokeswoman for, the women’s liberation movement in the late 1960s and 1970. Visit her official website here.