India’s Central Monitoring System (CMS): Something to Worry About?

-

Internet Governance

Maria Xynou

30 January 2014

The idea of a Panoptikon, of monitoring all communications in India and centrally storing such data is not new. It was first envisioned in 2009, following the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks. As such, the Central Monitoring System (CMS) started off as a project run by the Centre for Communication Security Research and Monitoring (CCSRM), along with the Telecom Testing and Security Certification (TTSC) project.

The Central Monitoring System (CMS), which was largely covered by the media in 2013, was actually approved by the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) on 16th June 2011 and the pilot project was completed by 30th September 2011. Ever since, the CMS has been operated by India’s Telecom Enforcement Resource and Monitoring (TERM) cells, and has been implemented by the Centre for Development of Telematics (C-DOT), which is an Indian Government owned telecommunications technology development centre. The CMS has been implemented in three phases, each one taking about 13-14 months. As of June 2013, government funding of the CMS has reached at least Rs. 450 crore (around $72 million).

In order to require Telecom Service Providers (TSPs) to intercept all telecommunications in India as part of the CMS, clause 41.10 of the Unified Access Services (UAS) License Agreement was amended in June 2013. In particular, the amended clause includes the following:

“But, in case of Centralized Monitoring System (CMS), Licensee shall provide the connectivity upto the nearest point of presence of MPLS (Multi Protocol Label Switching) network of the CMS at its own cost in the form of dark fibre with redundancy. If dark fibre connectivity is not readily available, the connectivity may be extended in the form of 10 Mbps bandwidth upgradeable upto 45 Mbps or higher as conveyed by the Governemnt, till such time the dark fibre connectivity is established. However, LICENSEE shall endeavor to establish connectivity by dark optical fibre at the earilest. From the point of presence of MPLS network of CMS onwards traffic will be handled by the Government at its own cost.”

Furthermore, draft Rule 419B under Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, allows for the disclosure of “message related information” / Call Data Records (CDR) to Indian authorities. Call Data Records, otherwise known as Call Detail Records, contain metadata (data about data) that describe a telecomunication transaction, but not the content of that transaction. In other words, Call Data Records include data such as the phone numbers of the calling and called parties, the duration of the call, the time and date of the call, and other such information, while excluding the content of what was said during such calls. According to draft Rule 419B, directions for the disclosure of Call Data Records can only be issued on a national level through orders by the Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of Home Affairs, while on the state level, orders can only be issued by the Secretary to the State Government in charge of the Home Department.

Other than this draft Rule and the amendment to clause 41.10 of the UAS License Agreement, no law exists which mandates or regulates the Central Monitoring System (CMS). This mass surveillance system is merely regulated under Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, which empowers the Indian Government to intercept communications on the occurence of any “public emergency” or in the interest of “public safety”, when it is deemed “necessary or expedient” to do so in the following instances:

-

the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India

-

the security of the State

-

friendly relations with foreign states

-

public order

-

for preventing incitement to the commission of an offense

However, Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, appears to be rather broad and vague, and fails to explicitly regulate the details of how the Central Monitoring System (CMS) should function. As such, the CMS appears to be inadequately regulated, which raises many questions with regards to its potential misuse and subsequent violation of Indian’s right to privacy and other human rights.

So how does the Central Monitoring System (CMS) actually work?

We have known for quite a while now that the Central Monitoring System (CMS) gives India’s security agencies and income tax officials centralized access to the country’s telecommunications network. The question, though, is how.

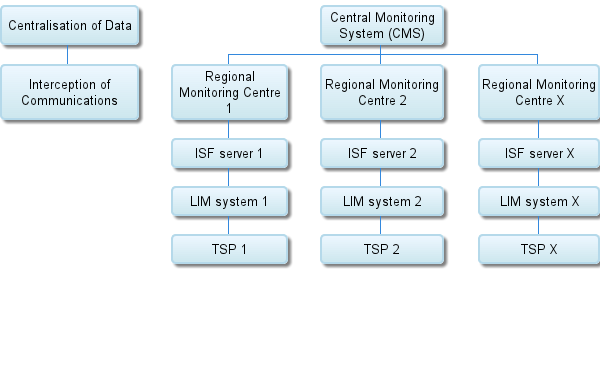

Well, prior to the CMS, all service providers in India were required to have Lawful Interception Systems installed at their premises in order to carry out targeted surveillance of individuals by monitoring communications running through their networks. Now, in the CMS era, all TSPs in India are required to integrate Interception Store & Forward (ISF) servers with their pre-existing Lawful Interception Systems. Once ISF servers are installed in the premises of TSPs in India and integrated with Lawful Interception Systems, they are then connected to the Regional Monitoring Centres (RMC) of the CMS. Each Regional Monitoring Centre (RMC) in India is connected to the Central Monitoring System (CMS). In short, the CMS involves the collection and storage of data intercepted by TSPs in central and regional databases.

In other words, all data intercepted by TSPs is automatically transmitted to Regional Monitoring Centres, and subsequently automatically transmitted to the Central Monitoring System. This means that not only can the CMS authority have centralized access to all data intercepted by TSPs all over India, but that the authority can also bypass service providers in gaining such access. This is due to the fact that, unlike in the case of so-called “lawful interception” where the nodal officers of TSPs are notified about interception requests, the CMS allows for data to be automatically transmitted to its datacentre, without the involvement of TSPs.

The above is illustrated in the following chart:

The interface testing of TSPs and their Lawful Interception Systems has already been completed and, as of June 2013, 70 ISF servers have been purchased for six License Service Areas and are being integrated with the Lawful Interception Systems of TSPs. The Centre for Development of Telematics has already fully installed and integrated two ISF servers in the premises of two of India’s largest service providers: MTNL and Tata Communications Limited. In Delhi, ISF servers which connect with the CMS have been installed for all TSPs and testing has been completed. In Haryana, three ISF servers have already been installed in the premises of TSPs and the rest of currently being installed. In Chennai, five ISF servers have been installed so far, while in Karnataka, ISF servers are currently being integrated with the Lawful Interception Systems of the TSPs in the region.

The Centre for Development of Telematics plans to integrate ISF servers which connect with the CMS in the premises of service providers in the following regions:

-

Delhi

-

Maharashtra

-

Kolkata

-

Uttar Pradesh (West)

-

Andhra Pradesh

-

Uttar Pradesh (East)

-

Kerala

-

Gujarat

-

Madhya Pradesh

-

Punjab

-

Haryana

With regards to the UAS License Agreement that TSPs are required to comply with, amended clause 41.10 specifies certain details about how the CMS functions. In particular, the amended clause mandates that TSPs in India will provide connectivity upto the nearest point of presence of MPLS (Multi Protocol Label Switching) network of the CMS at their own cost and in the form of dark optical fibre. From the MPLS network of the CMS onwards, traffic will be handled by the Government at its own cost. It is noteworthy that a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for MPLS connectivity has been signed with one of India’s largest ISPs/TSPs: BSNL. In fact, Rs. 4.8 crore have been given to BSNL for interconnecting 81 CMS locations of the following License Service Areas:

-

Delhi

-

Mumbai

-

Haryana

-

Rajasthan

-

Kolkata

-

Karnataka

-

Chennai

-

Punjab

Clause 41.10 of the UAS License Agreement also mandates that the hardware and software required for monitoring calls will be engineered, provided, installed and maintained by the TSPs at their own cost. This implies that TSP customers in India will likely have to pay for more expensive services, supposedly to “increase their safety”. Moreover, this clause mandates that TSPs are required to monitor at least 30 simultaneous calls for each of the nine designated law enforcement agencies. In addition to monitored calls, clause 41.10 of the UAS License Agreement also requires service providers to make the following records available to Indian law enforcement agencies:

-

Called/calling party mobile/PSTN numbers

-

Time/date and duration of interception

-

Location of target subscribers (Cell ID & GPS)

-

Data records for failed call attempts

-

CDR (Call Data Records) of Roaming Subscriber

-

Forwarded telephone numbers by target subscriber

Interception requests from law enforcement agencies are provisioned by the CMS authority, which has access to the intercepted data by all TSPs in India and which is stored in a central database. As of June 2013, 80% of the CMS Physical Data Centre has been built so far.

In short, the CMS replaces the existing manual system of interception and monitoring to an automated system, which is operated by TERM cells and implemented by the Centre for Development of Telematics. Training has been imparted to the following law enforcement agencies:

-

Intelligence Bureau (IB)

-

Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI)

-

Directorate of Revenue Intelligence (DRI)

-

Research & Analysis Wing (RAW)

-

National Investigation Agency (NIA)

-

Delhi Police

And should we even be worried about the Central Monitoring System?

Well, according to the brief material for the Honourable MOC and IT Press Briefing on 16th July 2013, we should not be worried about the Central Monitoring System. Over the last year, media reports have expressed fear that the Central Monitoring System will infringe upon citizen’s right to privacy and other human rights. However, Indian authorities have argued that the Central Monitoring System will better protect the privacy of individuals and maintain their security due to the following reasons:

-

The CMS will just automate the existing process of interception and monitoring, and all the existing safeguards will continue to exist

-

The interception and monitoring of communications will continue to be in accordance with Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, read with Rule 419A

-

The CMS will enhance the privacy of citizens, because it will no longer be necessary to take authorisation from the nodal officer of the Telecom Service Providers (TSPs) – who comes to know whose and which phone is being intercepted

-

The CMS authority will provision the interception requests from law enforcement agencies and hence, a complete check and balance will be ensured, since the provisioning entity and the requesting entity will be different and the CMS authority will not have access to content data

-

A non-erasable command log of all provisioning activities will be maintained by the system, which can be examined anytime for misuse and which provides an additional safeguard

While some of these arguments may potentially allow for better protections, I personally fundamentally disagree with the notion that a centralised monitoring system is something not to worry about. But let’s start-off by having a look at the above arguments.

The first argument appears to imply that the pre-existing process of interception and monitoring was privacy-friendly or at least “a good thing” and that existing safeguards are adequate. As such, it is emphasised that the process of interception and monitoring will “just” be automated, while posing no real threat. I fundamentally disagree with this argument due to several reasons. First of all, the pre-existing regime of interception and monitoring appears to be rather problematic because India lacks privacy legislation which could safeguard citizens from potential abuse. Secondly, the very interception which is enabled through various sections of the Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008, and the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, potentially infringe upon individual’s right to privacy and other human rights.

May I remind you of Section 69 of the Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008, which allows for the interception of all information transmitted through a computer resource and which requires users to assist authorities with the decryption of their data, if they are asked to do so, or face a jail sentence of up to seven years. The debate on the constitutionality of the various sections of the law which allow for the interception of communications in India is still unsettled, which means that the pre-existing interception and monitoring of communications remains an ambiguous matter. And so, while the interception of communications in general is rather concerning due to dracodian sections of the law and due to the absence of privacy legislation, automating the process of interception does not appear reassuring at all. On the contrary, it seems like something in the lines of: “We have already been spying on you. Now we will just be doing it quicker and more efficiently.”

The second argument appears inadequate too. Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, states that the interception of communications can be carried out on the occurence of a “public emergency” or in the interest of “public safety” when it is deemed “necessary or expedient” to do so under certain conditions which were previously mentioned. However, this section of the law does not mandate the establishment of the Central Monitoring System, nor does it regulate how and under what conditions this surveillance system will function. On the contrary, Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, clearly mandates targeted surveillance, while the Central Monitoring System could potentially undertake mass surveillance. Since the process of interception is automated and, under clause 41.16 of the Unified License (Access Services) Agreement, service providers are required to provision at least 3,000 calls for monitoring to nine law enforcement agencies, it is likely that the CMS undertakes mass surveillance. Thus, it is unclear if the very nature of the CMS falls under Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, which mandates targeted surveillance, nor is it clear that such surveillance is being carried out on the occurence of a specific “public emergency” or in the interest of “public safety”. As such, the vagueness revolving around the question of whether the CMS undertakes targeted or mass surveillance means that its legality remains an equivocal matter.

As for the third argument, it is not clear how bypassing the nodal officers of TSPs will enhance citizen’s right to privacy. While it may potentially be a good thing that nodal officers will not always be aware of whose information is being intercepted, that does not guarantee that those who do have access to such data will not abuse it. After all, the CMS appears to be largely unregulated and India lacks privacy legislation and all other adequate legal safeguards. Moreover, by bypassing the nodal officers of TSPs, the opportunity for unauthorised requests to be rejected will seize to exist. It also implies an increased centralisation of intercepted data which can potentially create a centralised point for cyber attacks. Thus, the argument that the CMS authority will monopolise the control over intercepted data does not appear reassuring at all. After all, who will watch the watchmen?

While the fourth argument makes a point about differentiating the provisioning and requesting entities with regards to interception requests, it does not necessarily ensure a complete check and balance, nor does it completely eliminate the potential for abuse. The CMS lacks adequate legal backing, as well as a framework which would ensure that unauthorised requests are not provisioned. Thus, the recommended chain of custody of issuing interception requests does not necessarily guarantee privacy protections, especially since a legal mechanism for ensuring checks and balances is not in place.

Furthermore, this argument states that the CMS authority will not have access to content data, but does not specify if it will have access to metadata. What’s concerning is that metadata can potentially be more useful for tracking individuals than content data, since it is ideally suited to automated analysis by a computer and, unlike content data which shows what an individuals says (which may or may not be true), metadata shows what an individual does. As such, metadata can potentially be more “harmful” than content data, since it can potentially provide concrete patterns of an individual’s interests, behaviour and interactions. Thus, the fact that the CMS authority might potentially have access to metadata appears to tackle the argument that the provisioning and requesting entities will be seperate and therefore protect individual’s privacy.

The final argument appears to provide some promise, since the maintenance of a command log of all provisioning activities could potentially ensure some transparency. However, it remains unclear who will maintain such a log, who will have access to it, who will be responsible for ensuring that unlawful requests have not been provisioned and what penalties will be enforced in cases of breaches. Without an independent body to oversee the process and without laws which predefine strict penalties for instances of misuse, maintaining a command log does not necessarily safeguard anything at all. In short, the above arguments in favour of the CMS and which support the notion that it enhances individual’s right to privacy appear to be inadequate, to say the least.

In contemporary democracies, most people would agree that freedom is a fundamental human right. The right to privacy should be equally fundamental, since it protects individuals from abuse by those in power and is integral in ensuring individual liberty. India may literally be the largest democracy in the world, but it lacks privacy legislation which establishes the right to privacy, which guarantees data protection and which safeguards individuals from the potentially unlawful interception of their communications. And as if that is not enough, India is also carrying out a surveillance scheme which is largely unregulated. As such, it is highly recommended that India establishes a privacy law now.

If we do the math, here is what we have: a country with extremely high levels of corruption, no privacy law and an unregulated surveillance scheme which lacks public and parliamentary debate prior to its implementation. All of this makes it almost impossible to believe that we are talking about a democracy, let alone the world’s largest (by population) democracy! Therefore, if Indian authorities are interested in preserving the democratic regime they claim to be a part of, I think it would be highly necessary to halt the Central Monitoring System and to engage the public and the parliament in a debate about it.

After all, along with our right to privacy, freedom of expression and other human rights…our right to freedom from suspicion appears to be at stake.

How can we not be worried about the Central Monitoring System?

The Centre for Internet and Society (CIS) is in possession of the documents which include the information on the Central Monitoring System (CMS) as analysed in this article, as well as of the draft Rule 419B under the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885.